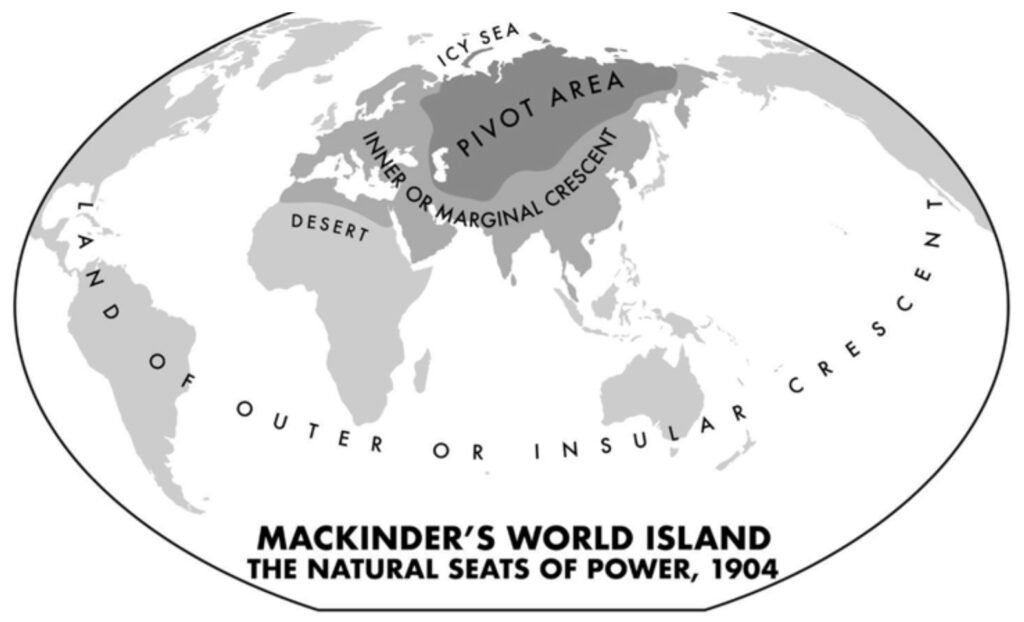

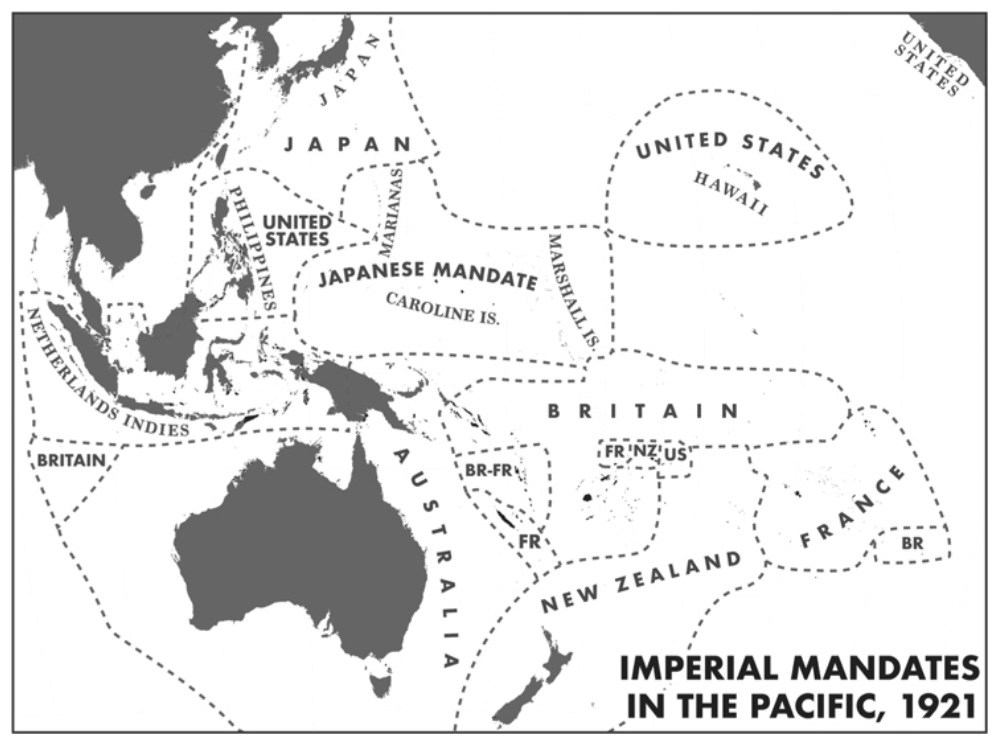

Yves here. I must confess to not having read Mackinder and even for those who have, Alfred McCoy’s analysis based on Mackinder’s “World Island” theory. A quick search did not turn up what I would very much like to have seen: an overlay of Mackinder’s “pivot area” with a map of modern Russia, as in what exactly lies out of Russia’s confines.

I hate to invoke Wikipedia, but it does list an important critique of Mackinder:

Mackinder only considered land and sea powers. In modern day time there are possibilities of attacking a rival without the need for a direct invasion via aircraft, long-range missiles, or even cyber attacks.

A blind spot, as opposed to lack of prescience, of Mackinder, lay in seeing Russia as technologically and even socially backwards, and not recognizing that Russia could and would catch up and even surpass the West in military prowess.

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

Image source: Alfred McCoy, To Govern the Globe, Chapter 1

We’re approaching the end of our look at Alfred McCoy’s To Govern the Globe, his examination of the centuries-long Western project to, well, govern the globe.

Links to previous parts of this series appear below:

Today we’ll examine a single persistent notion, an idea that has driven the West since the global project began — the domination of Asia, which Western strategists came to call the “world island.”

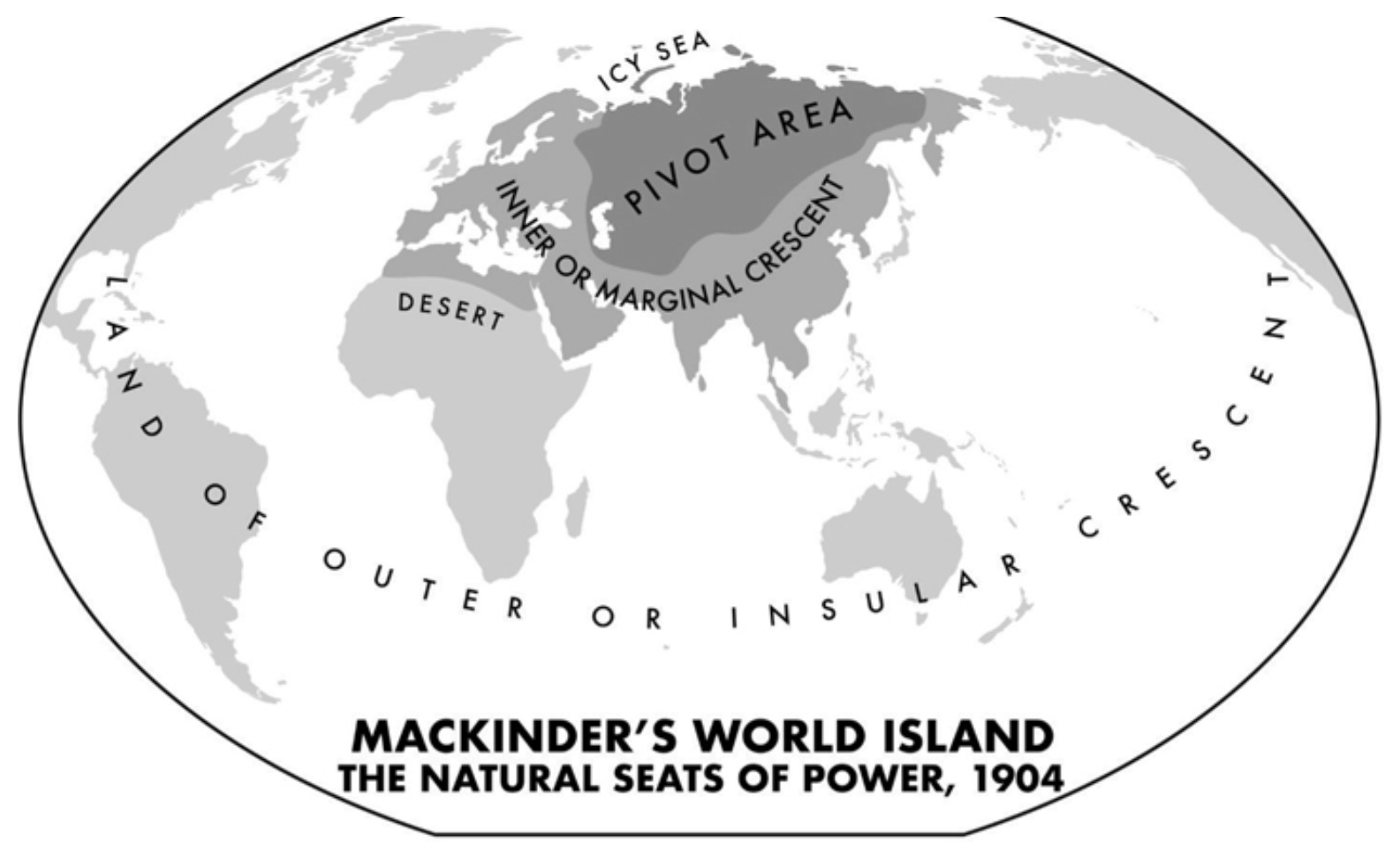

Consider the image below, from McCoy’s Chapter 2, “The Iberian Age.” It shows the Portuguese Empire circa 1570.

Note that while this is ostensibly a map of trade routes and ports — not military installations per se — it foreshadows what’s to come in Western thinking.

Note also that the ports and routes consist of two parts — those that dominate littoral (coastal) Africa to secure the Portuguese slave trade, and those that dominate littoral (coastal) Asia to secure access to that continent’s great wealth. (Littoral, noun and adjective, comes from the Latin for “shore.”)

Elimina Castle, or St. George Castle, Gold Coast (present day Ghana), from the Atlas Blaeu van der Hem, 1665-1668. The Portuguese established Elmina on the Gold Coast as a trading settlement in 1482. It eventually became a major slave trading post in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The Dutch seized the fortress from the Portuguese in 1637.

The slave trade eventually disappeared, but the domination of littoral Asia, the Asian coast, as a way to dominate the continent itself has informed Western strategists from that day through now. Why else do you think the West is today so upset about China building out islands in the South China Sea to use as bases? Answer: The West doesn’t want China to challenge Western control of its coast.

Image source

The West wants control for itself. The thinking behind dominating the coast of Asia goes way back. Let’s take a look through Alfred McCoy’s eyes.

What is Geopolitics

McCoy’s notion of “geopolitics” as a way of managing empires underlies the West’s whole strategy. From Chapter 1 (emphasis mine):

Geopolitics is essentially a method for the management of empire through the use of geography (air, land, and sea) to maximize military and economic advantage. Unlike conventional nations, whose peoples can be readily mobilized for self-defense, empires are, by dint of their extraterritorial reach and the perils inherent in the overseas deployment of armed forces, a surprisingly fragile form of government. They seem to require a strategic visionary who can merge landforms, seascapes, and societies into a sustainable global system, allowing such strengthened empires both extraordinary power and exceptional economic opportunity.

Empires are fragile and require extraordinary strategies to maintain. Hitler, for example, relied on the flawed geopolitical analysis of H.J. Mackinder — he thought the “world island” could be dominated by land — in his attempt to conquer post-Revolution Russia and prevent an Asian (Russia plus China) domination of Europe. That turned out badly.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, followed similar ideas when he armed Osama bin Laden and the Mujahideen in the late 1970’s in Afghanistan.

As an intellectual follower of Mackinder, Brzezinski would prove adept at applying the British don’s famous dictum about the geopolitical connection between Eastern Europe and Eurasia’s “heartland.”53 Wielding a multibillion-dollar CIA covert operation like a sharpened wedge, Brzezinski drove radical Islam from Afghanistan deep into Soviet Central Asia. That geopolitical gambit drew Moscow into a debilitating decade-long Afghan war, which weakened the Soviet Union sufficiently for Eastern Europe, three thousand miles away, to finally break free of its imperial grasp.

Brzezinski was proud of this move, even when, decades later, the chickens returned to the roost and these wars began to come home.

“What is most important to the history of the world?” [Brzezinski] asked in 1998. “The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some stirred-up Moslems or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the Cold War?”54

That’s geopolitics at work — modern attempts to dominate “the world island” by land or by sea. Needless to say, attempts to dominate by land have, all of them, failed.

Controlling the ‘World Island’ by Sea

Enter the American strategic thinker Alfred Thayer Mahan, a rather incompetent Navy captain and a more respected historian at the Naval War College. Mahan wrote extensively about the importance of sea power in the 1890’s, and his work formed the basis of American naval strategy in the Pacific from then until now. From Chapter 1 (emphasis mine):

When Washington [meaning the U.S.] took its first steps onto the world stage in the 1890s, an American naval historian, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, argued that sea power was, through the exceptional mobility of warships, the key to national security and international influence. His writings inspired Washington’s decision to build a blue-water navy and seize an empire of islands for naval bases stretching halfway around the globe, from Puerto Rico to Hawaii and the Philippines. Mahan’s international influence was extraordinary. His view that modern wars turned on a concentration of capital ships for a “decisive battle” would shape the strategies of Germany in World War I and Japan in World War II.46

Mackinder’s and Mahan’s geopolitical ideas formed the basis of modern strategic thinking. Those ideas even preceded their writings and properly describe the Western Project from its start.

If we combine Mahan’s emphasis on naval strength as the means to control continents with Mackinder’s focus on the “world island,” we will find that a succession of leading empires—Portuguese, Dutch, British, US, and Chinese—have all tried to achieve global power by dominating that tri-continental landmass of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Indeed, Portugal’s sixteenth-century chain of 50 fortified ports around Africa and across the Indian Ocean seems strikingly similar to China’s current string of 40 commercial ports covering much of the same terrain. Of course, China’s position has also been strengthened by a transcontinental grid of railroads and pipelines. Beneath the visible, much-discussed issues of trade and technology, this geopolitical strategy has become a battering ram for Beijing to break Washington’s control over Eurasia and thereby challenge its global hegemony.

The ‘Pax Americana’

This leads us to consider the present imperial age, what came to be called (by Americans) “Pax Americana.” That American Peace was, from the start, to be achieved through empire, and according to Mahan, the leading geopolitical thinker of his day, that empire rested on sea power. In America’s case, that meant the need to dominate strategic Pacific islands (emphasis mine):

Written at a time when America was just beginning its ascent to global power and expanding its navy, Mahan’s book made the crucial argument that Washington needed both to build a battle fleet and to capture island bases that could control the surrounding sea-lanes—particularly in the Pacific. In marked contrast to the Royal Navy’s chain of fortified bastions that made an “extensive empire, like that of England, secure,” US warships with “no foreign establishments, either colonial or military” would be “like land birds, unable to fly far from their own shores. To provide resting-places for them … would be one of the first duties of a government proposing to itself the development of the power of the nation at sea.”17 In reviewing the book for the Atlantic Monthly, a young Theodore Roosevelt wrote: “Captain Mahan shows very clearly the practical importance of naval history…. We need a large navy, composed not merely of cruisers, but containing also a full proportion of powerful battleships.”18

China and the Pacific Littoral

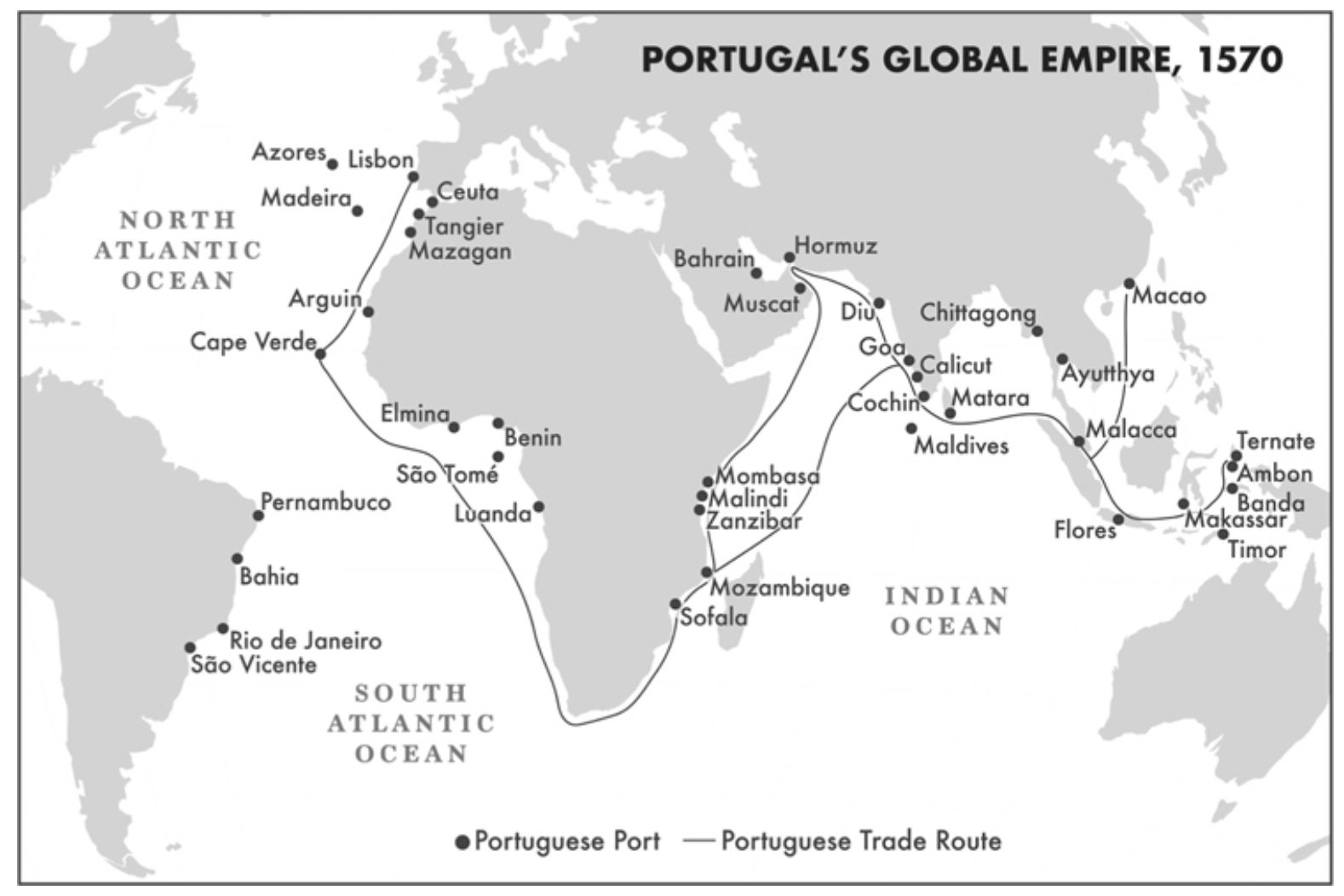

The book contains a lengthy and fascinating discussion of the way the U.S. came to rule the Pacific. Consider, for example, that in the 1920’s much of the West had claims (“mandates”) to Pacific territories.

But in the end, World War II, which closed a dying imperial age, that of the British, had birthed the aforementioned Pax Americana, the next new world order. And under the veneer of what McCoy calls “liberal internationalism” — which means, for example, the ideals behind the U.S.-led United Nations — lay the reality of consolidating and keeping power. On this contradictory stance, McCoy cites George F. Kennan, the chief architect of U.S. post-War foreign policy, who saw the situation clearly:

“We have about 50 percent of the world’s wealth but only about 6.3 percent of its population,” said George Kennan in 1947, when he was chief of policy planning at the State Department. “Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security. To do so, we will have to dispense with all … high-minded international altruism.”

U.S. global domination depended, then as now, on domination of the Pacific coast of Asia, the “Pacific littoral.” President Obama’s geopolitical strategy was to reduce American need for Middle East oil (a goal he accomplished) while simultaneously “pivoting toward Asia” and reinforcing our control of, you guessed it, the Asian coast.

As Obama withdrew troops from Afghanistan and Iraq, Washington began rebuilding its chain of military bases and strategic alliances along the Asian littoral. In March 2014, a full battalion of US Marines was deployed at the port of Darwin, Australia, on the Timor Sea, well positioned to access the strategic Lombok and Sunda Straits that lead to the South China Sea. Five months later, the two powers signed the US–Australia Force Posture Agreement allowing for the basing of American troops and warships at Darwin.158

Further north, in February 2016, the South Koreans completed a naval facility on Jeju Island, between that country and Japan, giving the US Navy access to a strategic port astride the East China Sea. Washington also signed an enhanced defense agreement with the Philippines, allowing use of several military bases astride the South China Sea.159 In combination with its eight established air and naval bases in Japan, Washington had effectively rebuilt its chain of military enclaves at the edge of Asia.160 To operate them, the Pentagon planned to “forward base 60 percent of our naval assets in the Pacific by 2020” along with a similar preponderance of Air Force fighters and bombers, which would be bolstered by “space and cyber capabilities.”161 By strengthening long-standing bilateral alliances, the Obama administration had taken the first steps, militarily speaking, toward rebuilding the US axial position on the Pacific littoral, which had long been central to its control over the vast Eurasian landmass.

Now perhaps we can understand the context of the Chinese reaction to these advances. The West has been encircling Asia with an eye to control since the mid-1400s. This is the Western Project, properly considered.

U.S. geopolitical strategy, from its earliest entry into the Western Project game, has been, explicitly, to control the Asian coast. It achieved that goal by the start of World War II, and by the end of the war and the years immediately following, achieved its strongest position to date in that region.

China, since the days of British domination, has worked to prevent Western domination of Asia. Its wish to build bases in the Spratley Island atolls are just the start of that struggle. This is what the conflict between the U.S. — inheritor of the Western Project — and China is actually about. It’s geopolitics American style.

The fight for control of Asia’s Pacific coast is six centuries old, and it will not end until the West has finally failed, or the inevitable chaos of climate makes mincemeat pie of everyone’s empire dreams. And now you know.