Many readers will probably say they don’t trust US economic statistics very much as it is, and as we’ll discuss, there are sound reasons to hold that view. But we’ll soon turn to economist Menzie Chinn explaining how their quality in the process of taking a further leg down thanks to DOGE spending-whacking and why that matters.

Even in the old days, one could see heavy-handed signs of manipulation. I recall, early in the dot-bomb era, an initial GDP release that depicted growth in the last quarter as 2.2% annualized. I was so offended that I called over a dozen well-networked people to ask if they saw any signs of any growth at all. None did and most had some contractionary sightings.

The final print for that quarter was 0.4%.

Similarly, in the runup to the financial crisis, there were considerable efforts to sell the “Goldilocks” economy (not too hot nor too cold but just right), followed by the “soft landing” thesis. Members of the then-vibrant econoblogosphere would debate the integrity of various new official releases in trying to judge underlying conditions. For instance, from a September 2007 post:

Those who have been following the job creation story weren’t surprised at the weak BLS employment (the so-called “non-farm payroll”) report today, or by the fact that it revised the results for the last three months downward by 81,000. Various commentators (see here, here, and here) have observed that the rises reported in recent months have been due almost entirely to a “voodoo calculation, the “birth/death model” a plug to allow for business creation and failure (one we’ve commented on before). Note this feature was added in 2001.

And where had these jobs supposedly been created? In construction. Need we say more?

Barry Ritholtz offered his latest observation about the birth/death model before the BLS report was released:

Considering how much softer the economy has been much in 2007 than last year, it is simply unconscionable that the B/D model has actually created more jobs in 2007 than it created at this point in 2006.

Year Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul

2006 -193 116 135 271 211 175 -57

2007 -175 118 128 317 203 156 26

Another favorite topic back then was the rate of inflation. John Williams of ShadowStats has done an admirable job of tracking over time the changes in how various official figures are calculated. Sadly, he does not have an independent data-gathering apparatus, so he has undermined the credibility of his fine historical work by attempting to produce his own alternative measures.

The twiddling with inflation figures has been in no small measure to reduce reported CPI to lower price of living adjustments, such as for Social Security. For instance, in the 1990s, Janet Yellen, then chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, pressed the Bureau of Labor Statistics to implement an inflation measure called chained CPI, which was widely understood to reduce reported inflation and hence Social Security inflation adjustments. The BLS did not implement it with respect to Social Security.

Another hot inflation data topic is hedonic adjustments. The notion is not entirely illegitimate; the question is how it is implemented. The notion is that when things like eggs get expensive, consumers will shift their purchases away from the newly-pricey good to other items. But there is a welfare loss in no longer being able to buy things like affordable eggs which critics contend that the hedonic adjustments don’t adequately reflect.

But there is another hedonic adjustment, not to prices but to output, which bizarrely has and continues to go under the radar. A recap in a 2012 post:

But the most important tidbit is later in the article, and it touches on hedonic adjustments to GDP, a topic that is not often discussed in polite company. We’ve covered this in greater depth before, for instance, in this 2007 post:

Let’s look at GDP. That’s a fundamental figure, surely beyond question or compromise. Really? Our GDP stats include something called a “hedonic price index” basically to allow for the fact that computers are becoming more powerful at lower costs. In essence, the US grosses up the price of computers in its GDP reports to adjust for the fact that computer prices are dropping.

These adjustments are significant. The US is the only country that uses hedonic indexing. The Bundesbank complained that if they calculated GDP the way we did, their GDP growth would be 0.5% higher. And the cumulative distortion is massive. In 2005, Michael Shedlock contacted the Bureau of Economic Advisers and they supplied some dated information on hedonics (including a spreadsheet). Even so, he found that hedonic adjustment to GDP was 2.257 TRILLION dollars, or 22% of then-current GDP.

With that as prelude, you might be tempted to view all economic-related figures as worthless. But that (at least up to now) is as naive as blindly trusting. Many are based on hard transactional data, like the ADP report on payrolls, or large-scale sampling. Others are imputed or derived, which is manipulation or just plain drift from reality can set in.

We’ll turn now to Chinn’s warning and then explain what we are likely to see even more of, which is news reports that rely on anecdata and hype as opposed to reasonably substantiated information. Mind you, we already have too much of that due to corporations and financial touts wanting to stoke optimism and with that, buying. We are entering an era of even fewer reality checks than before.

From Menzie Chinn:

The Commerce Department eliminated two advisory committees on economic statistics gathering (see Marketplace). BLS received some additional funds in March as part of a continuing resolution; however the Trump budget proposal includes an 8% reduction in budget in nominal terms.

The BLS, tasked with compiling the CPI as well as other labor market indicators (employment, wages) has been already stretched by stagnant funding colliding with escalating costs.

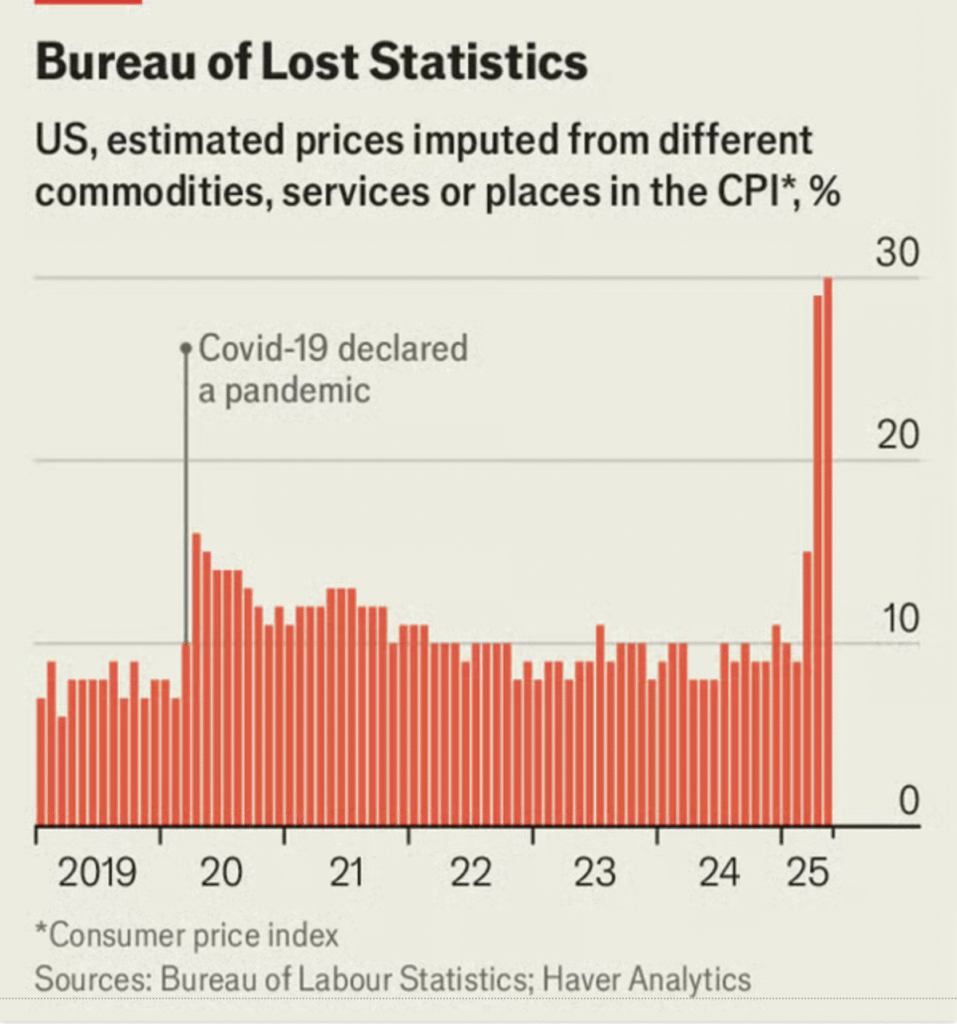

Recently, this has affected compilation of the CPI. More and more prices are imputed.

Source: Economist.

Of course, none of this should come as a surprise. A lot of this was prefigured in the Project 2025 (as I documented here).

There’s hardly any money to be saved by slashing in real terms funding for the statistical agencies, so one has to wonder what the underlying philosophy of the Trump administration is.

Perhaps, it’s the philosophy of “if a recession occurs, and it’s not measured, will anybody notice?” Perhaps, given Trump’s assault on the Fed’s independence, my guess is that it’s more likely “if inflation accelerates and inflation is not measured, will anybody notice?”.

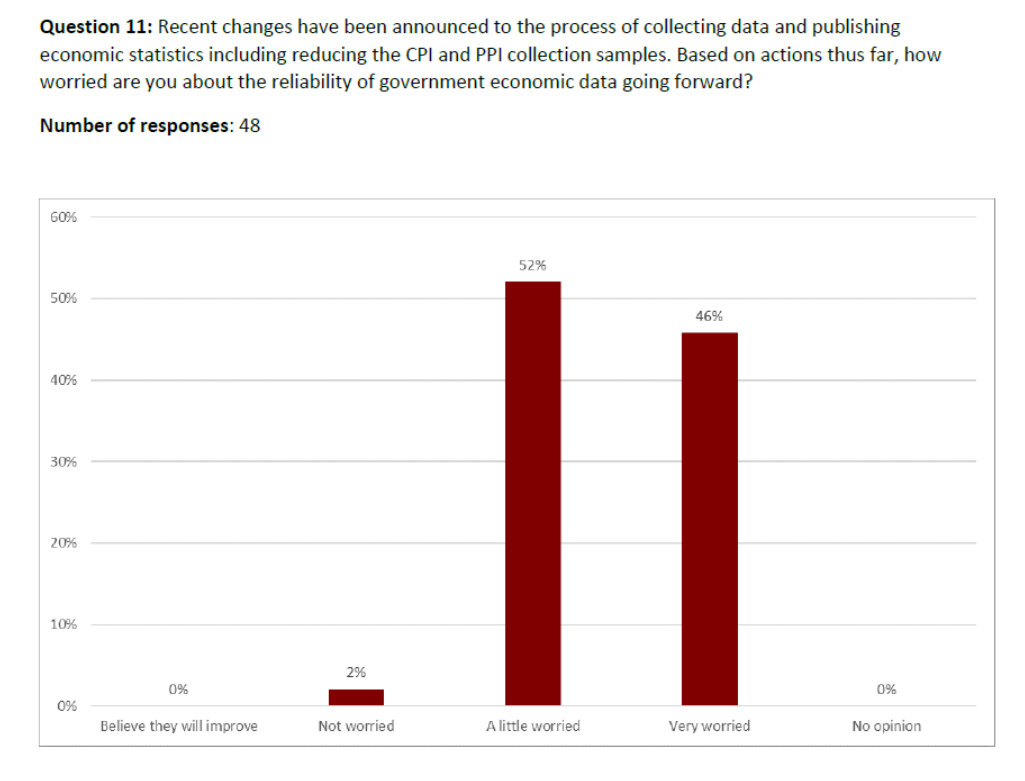

In any event, June’s FT-Booth survey of macroeconomists was interesting insofar as no one thought that the Administration’s measures would improve data quality.

Source: FT-Booth June Survey of Macroeconomists.

I was in the “very worried” category. Apparently, one macroeconomist would not be worried. I think he/she is in denial.

Some examples of why this type of crapification matters.

In the early 1980s, as a wee young thing at McKinsey, I was asked to value a US client’s possible acquisition of a stake in Mexican manufacturer. There was a massive gap between what the buyer and seller thought was a reasonable price.

I went to the Mexico City office to obtain information that would help with a valuation, such as help calibrate the buyer’s assumptions about growth and margins.

Within a couple of days of a week-long visit, I was storming around the office, complaining that there was no data in the entire Mexican economy.1

The consultants in the office agreed. One said, “We do a lot based on feelings.”

In a bit of serendipity, the Wall Street Journal is giving a big dose of what supposed economic stories based on feelings look like. Two days ago, its lead item was The U.S. Economy Is Regaining Its Swagger. The argument at the top of the piece:

Consumer sentiment collapsed. The S&P 500 stock index fell by 19% between February and April. The world held its breath and waited for the bottom to drop out.

But that didn’t happen. Now businesses and consumers are regaining their swagger, and evidence is mounting that those who held back are starting to splurge again.

The stock market is reaching record highs. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index, which tumbled in April to its lowest reading in almost three years, has begun climbing again. Retail sales are up more than economists had forecast, and sky-high inflation hasn’t materialized—at least not yet.

First, given that Trump was elected to a significant degree on a tide of voter upset about high inflation versus lackluster growth does not even remotely amount to “swagger” that can is allegedly being regained.

Second, placing a lot of stock in this stock market is also misguided. Admittedly, as Keynes warned, it can and will stay irrational longer than shorts might remain solvent. For a short form debunking, let us turn the mike over to Ed Zitron, from a wonderful piece we recommended:

The Magnificent 7 stocks — NVIDIA, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Apple, Meta, Tesla and Amazon — make up around 35% of the value of the US stock market, and of that, NVIDIA’s market value makes up about 19% of the Magnificent 7. This dominance is also why ordinary people ought to be deeply concerned about the AI bubble. The Magnificent 7 is almost certainly a big part of their retirement plans, even if they’re not directly invested.

Back in May, Yahoo Finance’s Laura Bratton reported that Microsoft (18.9%), Amazon (7.5%), Meta (9.3%), Alphabet (5.6%), and Tesla (0.9%) alone make up 42.4% of NVIDIA’s revenue. The breakdown makes things worse. Meta spends 25% — and Microsoft an alarming 47% — of its capital expenditures on NVIDIA chips, and as Bratton notes, Microsoft also spends money renting servers from CoreWeave, which analyst Gil Luria of D.A.Davidson estimates accounted for $8 billion (more than 6%) of NVIDIA’s revenue in 2024. Luria also estimates that neocloud companies like CoreWeave and Crusoe — that exist only to prove AI compute services — account for as much as 10% of NVIDIA’s revenue.

NVIDIA’s climbing stock value comes from its continued revenue growth. In the last four quarters, NVIDIA has seen year-over-year growth of 101%, 94%, 78% and 69%, and, in the last quarter, a little statistic was carefully brushed under the rug: that NVIDIA missed, though narrowly, on data center revenue. This is exactly what it sounds like — GPUs that are used in servers, rather than gaming consoles and PCs (.….

NVIDIA’s quarter-over-quarter growth has also become aggressively normal — from 69%, to 59%, to 12%, to 12% again each quarter, which, again, isn’t bad (it’s pretty great!), but when 88% of your revenue is based on one particular line in your earnings, it’s a pretty big concern, at least for me. Look, I’m not a stock analyst, nor am I pretending to be one, so I am keeping this simple:

- NVIDIA relies not only on selling lots of GPUs each quarter, but it must always, always sell more GPUs the next quarter.

- 42% of NVIDIA’s revenue comes from Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, Alphabet and Tesla continuing to buy more GPUs.

- NVIDIA’s value and continued growth is heavily reliant on hyperscaler purchases and continued interest in generative AI.

- The US stock market’s continued health relies, on some level, on five or six companies (it’s unclear how much Apple buys GPU-wise) spending billions of dollars on GPUs from NVIDIA.

- An analysis from portfolio manager Danke Wang from January found that the Magnificent 7 stocks accounted for 47.87% of the Russell 1000 Index’s returns in 2024 (an index fund of the 1000 highest-ranked stocks on FTSE Russell’s index).

In simpler terms, 35% of the US stock market is held up by five or six companies buying GPUs. If NVIDIA’s growth story stumbles, it will reverberate through the rest of the Magnificent 7, making them rely on their own AI trade stories.

And Zitron soon gets to the punch line (in enormous font size:

The Magnificent 7’s AI Story Is Flawed, With $560 Billion of Capex between 2024 and 2025 Leading to $35 billion of Revenue, And No Profit

To put this more simply, the sort of bounce the US is seeing is a reversal of a Trump-induced panic. A colleague who has contacts in many industries dismissed the Journal’s cheery take as “Anecdotes and animal spirits.” And contra the Journal, we’ve had many reports from readers via e-mails and in comments of US businesses seeing big drops in activity, not reversed much of late, and considering or engaging in cutbacks. So which version of the feelings about where things stand to believe?

The very next day, the lead Journal story was more flagrant boosterism. From The Global Economy Is Powering Through a Historic Increase in Tariffs:

The global economy is sailing through this year’s historic increase in tariffs, displaying an unexpected trait: resilience.

Faced with extreme uncertainty, businesses and households have surprised economists with their ability to hedge, finding a short-term path through as they await clarity on where tariffs will end up.

Global producers brought forward purchases and rerouted goods destined for the U.S. through third-party countries that are subject to lower tariffs. For the most part, households and businesses have continued to spend and invest despite the uncertainty, analysts say.

The world economy grew at a 2.4% annual rate in the first half of this year, around its longer-term trend, according to JPMorgan.

Trade volumes are buoyant, stock markets on both sides of the Atlantic have rebounded to record highs and growth forecasts from Europe to Asia are being raised.

Lordie. In January, the IMF predicted global growth for 2025 and 2026 to come in at 3.3%. A mere 2.4% is a big miss, not something to brag about unless you are a market tout serving easily manipulate clients (as in most equity investors).

And the IMF revised its forecasts in April based on Trump’s tariff announcements….and had its new 2025 global forecast at 2.8%! In other words, the world economy is doing worse in the face of the Trump tariff shock, with his high and arbitrary Liberation Day levels, than experts expected.

____

1 There was actually a smidge. Public companies traded at either two or four times earnings.